The current and dominant view of the economy espoused by the neo-classical individualist view of economics, argues that much of human interaction is about the “science of choice”. Indeed, in the words of left-leaning Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang, the neo-classical take on humanity is such that:

“Choices are made by individuals, who are assumed to be selfish, only interested in maximising their own welfare – or at most that of their family members. In doing so, all individuals are seen to make rational choices, namely, they choose the most cost-efficient way to achieve a given goal”.

Put another way, neo-classical economic theory assumes individual humans are self-seeking toads. And this might be true. Certainly you would think so if you had met my neighbours, as fat as butter to borrow from Shakespeare’s Henry IV, seemingly oblivious to my neighbourly protestations concerning their barking canines (which I have named Thing 1 and Thing 2 to borrow from that other great of literature, Dr Seuss). Induitably, I have often alluded to the egocentric nature of Vienna (driving, sun-beds, standing in queues – the legitimate hallmarks of any serious social scientific research) and have seen first-hand what the pressures of living in the number one city in the world can do to perfectly rational and sensible fellow citizens. Namely, turn some of them into insufferable zealots (although I concede this may just be a symptom of living in any city and only the driving, sun-beds and queuing is unique to Wien).

Yet I know that neo-classical notions of individuality and the pursuit of personal utility at the expense of everyone and everything else is nothing more than academic masturbation. I know this because I have just returned from hospital, a publicly funded Viennese hospital, part of a healthcare system that might be imperfect (like every and any system) but staffed by the kinds of people and teams where notions of human agency based on actions of self-survival and individual propagation are anathema.

One only has to experience a length of time in such a hospital to know that human nature – for some – is so much more than a science of choice and distending of personal wellbeing. And in spite of having a piece of my face cut off, I feel more strongly than ever about the palpable potential for a collective human spirit as something wholly unrecognisable in any theory espousing political and moral individualism.

But how did we get here? To put it simply it was a misdiagnosis (me, not Vienna). If you cast your minds back to May of this year, I wrote about a visit to the doctor (see A Pint of Patience). This was prompted by a tiny itching on my nose which was dismissed as nothing more than a tiny itch on my nose. However, over the summer the diminutive itch persisted which necessitated a second opinion. So, after seeking the highly reliable therapeutic guidance of my mother-in-law, I took myself to another Hautärzt (literally – skin doctor).

The Austrian health system, like much of Europe and beyond is universal, meaning you do not pay at the point of entry and the money is stolen from your salary to finance it and other social scroungers (to paraphrase my Texan buddies). Normally this means if you need something special, you first visit your Familienärzt (general practitioner) who will provide you with an Überweisung which is the required document referring you to a specialist (or specialists). So recently I obtained one for blood tests, x-rays, and ultra-sound, although I was pretty sure I wasn’t pregnant. Assuming you then need to progress to hospital, this paperwork is the basis for your admission and often one of your specialists will also work there – most maintain a practice (or Ordination) and moonlight down the Krankenhaus.

Naturally, if you can pardon the pun, there is a thriving private health industry (I have seen the plastic beauty surgeons and their creations on reality television) where you turn up and hand over your cash for the briefest of consultations and a quick nip and tuck. But like our Swiss cousins to the west, there is also a parallel, semi-private system whereby you can attend something called a Wahlärzt, a doctor without a contract with a state insurance provider. In such cases, you pay a bill upfront – about a hundred Euro on average – and then claim back part of the cost from your social insurance. (In economics this is called a “hurdle”. Like croissants, Vienna invented hurdles.) How much you get back is based on what the state provider would pay if you chose a doctor with a social insurance agreement. So, a visit to my GP is worth 29 Euro in my system which is what I would get back if I went semi-private irrespective of the cost of the private doctor.

But it depends on the ailment and field of medicine. In my limited experience it can be anything from 20 percent to 70 percent (children seem to get more although many inoculations are also not free). However, it enables you to see a very competent medic very quickly and waiting times are generally reduced to a minimum as the doctor does not have to piss about – the aesculapian term – with the giants of social medical care.

I can only assume the upfront ninety or more Euro fee is largely responsible for this. I could not readily afford such outlays every time I needed a prescription or a check-up but it seemingly has the intended effect of expedience. In the sense that when faced with a medical need, the very thought of immediately handing over cash (one doctor I knew actually asked if I needed to go to the Bankomat) is a sobering reminder that there is an indisputable cost, like it or not, to healthcare provision. And this monetary whiff of the smelling salts has an instant effect enabling the patient – you – to question whether the patient – you – is being trivial in your application of the tax funded health system. I refer not so much to the semantically fashionable “health tourist”, more the entrenched citizen who has taken a suite in a neighbourhood hotel and insists on daily visits and a chinwag for the most minor of complaints. Therefore, ninety Euro for a sniffle and a mild headache? Probably not. Ninety Euro for a pain in your kidneys after getting married? Probably yes.

In any case, you may argue that this is okay for those that can pay. Of course, I know most of you do not want to engage in an extended debate about the moral application of healthcare for all. You want Mozart Balls, Christmas markets and poorly exposed pictures of sausage stands. But in almost every case (apart from my obese friends next door, immorally driving up my taxes with their ill-health) I wouldn’t disagree. Healthcare should be available to all and the best system is through a central pot where hopefully, like most insurance, you will never need it.

However, as my dentist pointed out only this month, right at the moment he had that sharp object somewhere deep between my gums and teeth, people will happily spend a hundred Euros on a pair of shoes, or a pair of jeans, or a smartphone, or any other shit we most certainly don’t need, but find it abhorrent to spend the equivalent on a twice-yearly deep clean of their mouths. What he was getting at, drill approaching my teeth as flashes of Marathon Man consumed my consciousness, is that we need a little bit of perspective and a re-balancing of personal priorities and expenditure with regard to matters of modern health. It is a contention I find myself increasingly drawn to whatever the cost to my shoe collection, and, as I laid there prostrate in a leather chair, gripping the armrests with the force of Thor, I nodded vigorously in agreement, total, complete, don’t hurt me agreement.

(Just for the record: the treatment I refer to at the dentist, the deep hygiene cleaning, is not covered by any Viennese Krankenkasse (social insurance system). Everyone has to pay. The cost is the same as my car insurance for one month. And that is the point of my affable cycling Zahnärzt.)

And so back in September I arranged an appointment at another dermatologist (a Wahlärzt) for, as it turns out, the crucial second opinion. Her first impression was a veritable bombshell (a word beginning with c that some people in Vienna seem to think rhymes with “dancer”). But a histology report would confirm either way. In any case, it was the kind of abnormal cell growth, almost certainly a result of sun exposure – the bastard Freibad again! – which although needed removal to prevent my metamorphosis into the Elephant Man, was almost always local and nothing to fret about. So, like Sean Connery in Goldfinger, I was strapped down and a laser removed some of my nose for analysis.

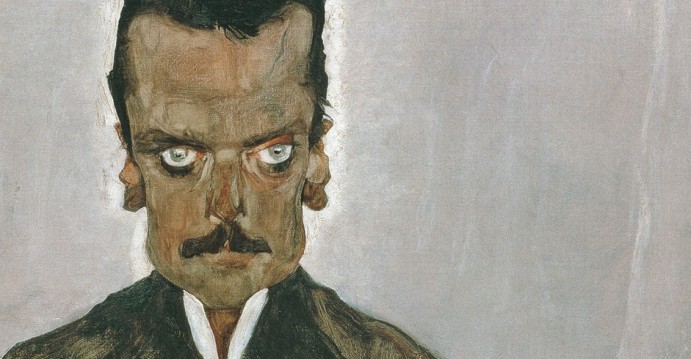

With the smell of singed skin accompanying me as I made my way out the door, I handed over some cash with a feeling that bared little resemblance to the gaiety I felt back in May and my last visit to Herr Doktor Skin. Worse, given the location of the offending aberration (the tumour not the original myopic doctor), I would have to have an operation by a surgeon skilled in the art of facial reconstruction. In the words of my new ninety-Euro-a-visit dermatologist, I didn’t want a Pfusch (bodge job) where the outcome was possible mutilation and an end to my chances of appearing on Austria’s Next Top Model. Worse still, I wasn’t even off to the pub on this occasion to numb any residual pain with lager.

But still. Those memories of handing over nearly a quarter of my income these last fourteen years to the Viennese SVA (my social insurance taskmasters) was suddenly starting to look like one bet that would soon pay off. I entertained thoughts of finally taking off a week of work legitimately convalescing (this appealed to me more than I can put in words without being sued). And most importantly I was going to taste hospital food. Momentarily buoyed by these thoughts, I picked up the card for the plastic surgeon the dermatologist had kindly provided and keyed in the digits. In German: “The number you have dialled does not exist”. Oh crikey. Oh very, bloody crikey …

Continued in part 2.

© RJ Barratt 2014